Banking Bad: Tulip Mania, The Greatest Bubble Story of All Time

Banking Bad: Tulip Mania, The Greatest Bubble Story of All Time

The Wallet podcast is back, and we’ve got something new in store for you. You’re familiar with our interviews with financial experts, money enthusiasts, and top investing lessons, but we decided to spruce things up a bit and do something different. Over the next 6 weeks, we’re introducing a series titled 'Banking Bad' - an entirely new format! Get ready for tales of socialite financial abuse, debt struggles, gambling addictions, the rollercoaster world of meme stock investors, and true financial crime stories.

We’re used to hearing about stocks, credit or commodities being at the centre of bubbles, but never a flower. Today, we’ll be looking at tulip mania - a period in the 1630s when the prices of tulip bulbs in the Netherlands soared to unprecedented levels, driven by a speculative frenzy.

Anne Goldgar, an American historian and academic, argues that tulip mania was not a widespread frenzy that affected the whole society, but rather a limited phenomenon - and that accounts of the subsequent crash may be more fiction than fact. However, there are key takeaways from this story that we, as investors, can learn from.

***

You can listen (19 min) and subscribe here:

“Goldgar’s theory is based on extensive archival research, in which she examined thousands of documents related to the tulip trade, such as contracts, inventories, letters, diaries, and court records. She found that the tulip mania was not as widespread or destructive as it has been portrayed.”

The tulip mania was a period in the early 17th century when the prices of tulip bulbs in the Dutch Republic soared to unprecedented levels, driven by a speculative frenzy and a new form of futures trading. Tulips, which were introduced from Turkey and Central Asia, were highly prized for their beauty and rarity, especially those with unusual colours and patterns.

Some of the most coveted varieties, such as the Semper Augustus, could fetch more than 10 times the annual income of a skilled artisan. This was due to a virus that created especially unusual colours in the tulips.

The demand for tulips was so high that people started to buy and sell contracts for future delivery of bulbs, without ever seeing or possessing them.

This created a market bubble that inflated the prices even further, until they reached a peak in February 1637.

Then, suddenly, the bubble burst, as buyers became unwilling or unable to honour their contracts, and the prices collapsed. Many investors lost their fortunes, and the tulip trade declined sharply. The episode is considered to be the first recorded example of an economic bubble in history.

Anne Goldgar

What exactly caused it?

There are many factors that contributed to the rise and fall of the tulip mania. Some of them are:

The novelty and scarcity of tulips: Tulips were new and exotic plants that fascinated the Dutch people with their variety and elegance. They were also difficult to cultivate and propagate, making them scarce and valuable. The rarest and most desirable tulips were those that had multicoloured petals, caused by a virus infection that was unknown at the time. These tulips were called “broken” or “flamed” and were seen as symbols of status and wealth.

The social and economic context: The Dutch Republic was experiencing a golden age of prosperity, trade, art, and science in the 17th century. It was one of the most powerful and wealthy nations in Europe, with a flourishing merchant class and a liberal culture. The Dutch people had a high standard of living and a taste for luxury goods, such as fine art, porcelain, spices, and tulips. They also had access to credit and banking systems that facilitated commerce and speculation.

The innovation of futures trading: The tulip trade was not only based on the exchange of actual bulbs, but also on the trade of paper contracts that promised future delivery of bulbs at a fixed price. These contracts were called “florins” or “warrants” and were traded in taverns or exchanges called “colleges”. This allowed people to speculate on the future price movements of tulips without having to own or store them. It also enabled people to leverage their investments by borrowing money or selling contracts short (i.e., selling contracts they did not own in hopes of buying them back at a lower price later).

The psychology of speculation: The tulip mania was driven by herd behaviour among investors. People bought tulips not because they valued them as flowers, but because they expected to sell them at a higher price to someone else. As more people joined the market, the prices rose higher and higher, creating a positive feedback loop that reinforced the belief that tulips were a sure way to make money. People also suffered from cognitive biases, such as overconfidence, confirmation bias, and loss aversion, that distorted their perception of reality and risk.

What are the controversies around tulip mania?

Anne Goldgar is a American historian, author and academic, specializing in seventeenth and eighteenth century European cultural and social history, and of Francophone culture across Europe. She holds the inaugural Van Hunnick Chair in European History at the University of Southern California Dornsife

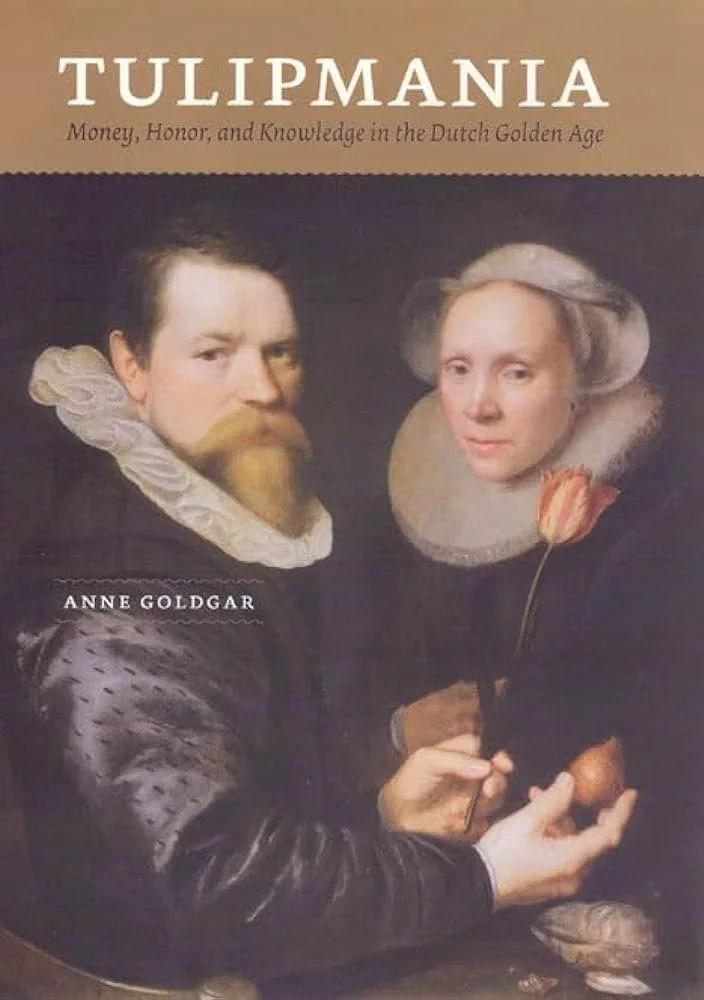

She is the author of the book Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age, which challenges the traditional account of tulip mania as a massive and irrational economic bubble that ruined many people in the 17th century.

According to Goldgar, most of what we have heard about tulip mania is not true. She argues that the evidence for the bubble is based on biased and unreliable sources, such as satirical pamphlets and moralistic sermons that exaggerated the extent and impact of the phenomenon. She also points out that tulips were not the only flowers that had high initial prices when they were introduced in Europe, and that the Dutch economy was not significantly affected by the collapse of the tulip market.

Goldgar’s theory is based on extensive archival research, in which she examined thousands of documents related to the tulip trade, such as contracts, inventories, letters, diaries, and court records. She found that the tulip mania was not as widespread or destructive as it has been portrayed. She claims that only a small group of people, mostly wealthy merchants and artisans, were involved in the speculative trade of tulip bulbs, and that they did not lose their fortunes or livelihoods when the prices fell.

She also found that the tulip trade was not driven by irrational exuberance or greed, but by social and cultural factors, such as honour, reputation, knowledge, and curiosity.

Goldgar’s theory of tulip mania is a revisionist and controversial one, as it contradicts the popular and historical narrative that has been repeated for centuries. However, it also offers a more nuanced and realistic view of the tulip mania, as well as a deeper understanding of the Dutch society and culture in the Golden Age.

Human behaviour

Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age

The tulip mania is a cautionary tale that warns us about the dangers of speculation and irrationality in financial markets. It shows us how human emotions can influence our decisions and behaviour in ways that are not always rational or optimal.

It also shows us how social factors, such as peer pressure, imitation, conformity, and reputation, can affect our choices and actions in markets.

Moreover, it shows us how technological innovations, such as new forms of trading or communication, can create new opportunities but also new challenges and risks for investors.

Lessons for investors

Investing is not a game or a gamble. It is a long-term strategy to grow your wealth and achieve your goals. But it also requires caution and discipline. You should not chase after investments or assets that promise quick profits, as they may turn out to be bubbles or scams. We have seen this happen recently with cryptocurrencies, for example.

To help you avoid these pitfalls, I have compiled a list of 10 golden rules for investors:

Diversify your portfolio across different asset classes (stocks, bonds, real estate, etc.) to reduce risk.

Have a plan with clear goals, risk tolerance, and time horizon.

Invest for the long term (usually 5 years +), as it can smooth out market volatility and compound your returns.

Do your research and educate yourself: Never invest in something you don’t understand or can’t explain.

Understand risk: Only invest money you can afford to lose. Be prepared for market fluctuations and see them as opportunities.

Think independently: Don’t follow the herd or the hype. Make decisions based on your research and goals.

Review and rebalance your portfolio regularly to align it with your goals.

Watch out for fees: High fees can eat into your returns. Look for low-cost investment options like index funds or ETFs.

Consider passive investing: You can automate your investments, prioritising funds over individual stocks, and avoid emotional trading.

Learn from your mistakes: It’s normal to make some investment errors, but don’t let them discourage you or stop you from investing.

****

RESOURCES:

Anne’s book: Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age

Follow Anne on X @anne_goldgar

SPONSOR:

Thank you to our partner PensionBee: combine, contribute and withdraw online. Take control of your pension, so that you can enjoy a happy retirement and join 223,000 customers saving with PensionBee. When investing, your capital is at risk. Investments can go down as well as up, and you may get back less than you invest.

OTHER EPISODES OF BANKING BAD:

#1 Brooke Astor, and When Financial Abuse Hits Home

#2 Tulip Mania, The Greatest Bubble Story of All Time

#3 How I Ended Up £250,000 in Debt

#4 Surviving the Dotcom Bubble with Martha Lane Fox of Lastminute.com

#5 GameStop, How Reddit Users Brought Wall Street to its Knees